Related Downloads

Related Links

Additional

Outcomes

39. We sought to assess the quality of service provided by COPFS to those making enquiries. To do this, we considered evidence from a range of sources, including Enquiry Point performance data, the results of our contact audit, and service user feedback. We also considered whether COPFS itself understands how well it responds to enquiries.

Performance

40. As would be expected in a contact centre environment, a range of data is available about Enquiry Point’s call handling. This data is discussed at Enquiry Point manager and team meetings. It is used to monitor the performance of the service and of individual operators.

41. The introduction of a new contact centre application in 2022 affected the range and quality of the data gathered by Enquiry Point.[12] The change in systems means it is difficult to compare data with previous years and to identify long-term trends. Difficulties encountered with the introduction of the new application resulted in a lack of robust data and a lack of capacity to analyse and monitor data for some months. For those reasons, the data presented in this report is limited. We have focused on call handling data for the year between October 2023 and September 2024. During this period, the application had begun to stabilise and there was greater confidence in the quality of the data.

42. Unfortunately, very limited data is available about enquiries received via email, meaning COPFS has only a partial picture of the service delivered by Enquiry Point. In addition, the call handling data relates only to the service provided by Enquiry Point. No data is available about the handling of enquiries if they are passed to another team within COPFS for resolution.[13]

Performance data

43. While a range of data is available about Enquiry Point’s call handling, we have focused only on some key measures, including:

- total volume of calls (also known as ‘calls presented’)

- calls queued

- calls abandoned

- queue time

- calls handled

- call handling time.

44. Enquiry Point’s performance is affected by a range of factors, including:

- the volume of calls, including fluctuations in demand according to the day of the week and time of day

- the number of operators available to answer calls. This will be influenced by general resourcing for the service as well as operators taking annual or sick leave

- staff turnover and the number of experienced operators available to answer calls versus those who are new and inexperienced. Even when experienced operators are available, their productivity will be reduced if they are training newer colleagues

- system issues.

45. Changes in performance can be correlated to the number of operators available to answer calls and known system outages.

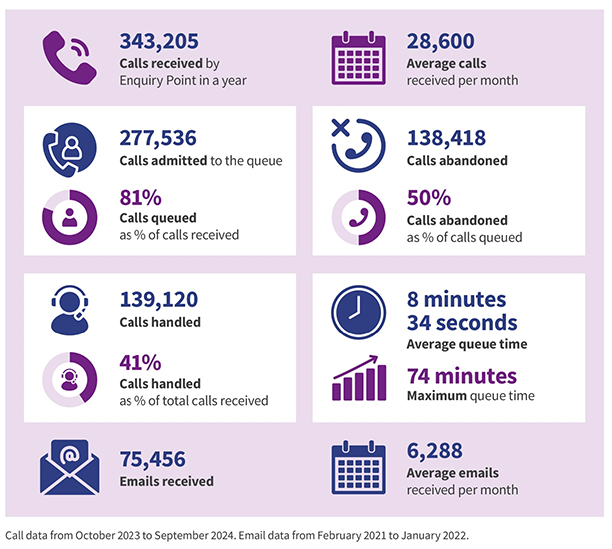

46. Total volume of calls. In the year between October 2023 and September 2024, the total number of inbound calls made to Enquiry Point during its opening hours was 343,205. The average for each month was 28,600. There are considerable fluctuations between months. This will be influenced by the number of days, weekends and public holidays in a month. The number of calls received each month ranged from 18,578 (in December 2023) to 35,616 (January 2024).

47. Calls queued. Enquiry Point limits the number of calls that enter its queue. This is to avoid callers joining a lengthy queue and having to wait too long for their call to be answered. When the queue is full, the caller is thanked for calling and asked to call back later or email and the email address is provided. The size of the call queue can be adjusted depending on staffing levels. We heard that the standard call queue size had previously been 50, but that this had been reduced to 30 in 2021.

48. In the year between October 2023 and September 2024, the number of calls admitted to the queue was 277,536. This means 81% of calls made were admitted to the queue. Again the number of calls admitted to the queue fluctuated each month. It ranged from 14,458 (December 2023) to 28,621 (January 2024). The average was 23,128 per month.

49. During that period, 65,669 calls were not admitted to the queue. This was an average of 5,472 calls per month. These were callers who were effectively turned away, albeit some may have called back another time or made their enquiry by email instead.

50. Calls abandoned. Once admitted to the queue, some callers hang up and abandon the call. Data on calls abandoned can be an indicator that the queue length is too long and that callers are looking for a quicker response. Among those who responded to our survey were those who abandoned their call because they were frustrated it was not answered in a reasonable time. Between October 2023 and September 2024, the number of calls abandoned was 138,418. This meant 50% of all calls queued were abandoned.

51. Of these abandoned calls, 80,437 were abandoned within 10 seconds (this was 29% of all calls admitted to the queue). Such calls may have been to a wrong number or, if to the correct number, it seems the caller hung up after not receiving an immediate response.

52. The number of calls abandoned each month ranged from 4,460 (December 2023) to 16,696 (August 2024). The average number of calls abandoned each month was 11,535.

53. Queue time. Enquiry Point monitors the average time callers spend in the queue as well as the maximum time a caller has spent in the queue before having their call answered by an operator. Between October 2023 and September 2024, the average queue time was eight minutes and 34 seconds. The average queue time per month ranged from five minutes (December 2023) to 13 minutes (July 2024).

54. The maximum time a caller spent in the queue during the year was 74 minutes. On the day this call was made, Enquiry Point experienced a failure in its contact centre application. Aside from this call, the longest time a caller spent in the queue during the year was 45 minutes.

55. The average queue time for calls that were abandoned during the year was two minutes. The longest a caller waited in the queue before abandoning their call was 62 minutes. This call took place on the same day that Enquiry Point experienced the system failure noted at paragraph 54. Aside from this call, the longest time a caller waited in the queue before abandoning their call during the year was 55 minutes.

56. Calls handled. This is the number of calls that are connected to an operator. Between October 2023 and September 2024, Enquiry Point handled 139,120 calls, an average of 11,593 calls per month. The highest number of calls handled in a month was 13,453 (November 2023) while the lowest was 9,998 (December 2023).

57. Call handling time. Enquiry Point measures the time it takes to handle calls. This is measured from the point the caller is connected to an operator, to the point the operator concludes the call. It does not include any time the caller spends talking to another member of staff if they are transferred to another team. During the year, the average call handling time was seven minutes and 15 seconds.

Enquiry Point performance

Key performance indicators and targets

58. Enquiry Point’s call handling data is used to assess performance against the service’s key performance indicators and targets. Enquiry Point has two key performance indicators (KPIs):

- to handle 90% of inbound calls presented (KPI 1)

- to answer 80% of enquiries at first point of contact (KPI 2).

- It also has two targets for operators:

- to handle 40 calls per day

- to ensure callers are on hold for no more than three minutes when attempting to transfer them to another team, and for no more than five minutes when searching case management systems for information or seeking guidance to answer their query.

60. In relation to KPI 1 (handling 90% of inbound calls presented), this is a longstanding KPI that Enquiry Point has persistently been unable to meet. Between October 2023 and September 2024, Enquiry Point handled 71% of calls presented. The highest monthly performance was 80% in December 2023 while the lowest was 63% in August 2024.

61. It is worth noting that the KPI is not based on all calls made to Enquiry Point, but only those that enter the call queue. It also excludes calls that enter the queue and that are abandoned within 10 seconds as Enquiry Point has had limited opportunity to answer them. When the Enquiry Point phone line is switched off each day, operators work until all the calls in the queue are answered. As well as the 37% of callers in the queue whose call was not handled by Enquiry Point in August 2024, there were others whose call was not handled because it never entered the queue. In August 2024, more than 5,000 calls did not enter the queue.

62. Older data shows that Enquiry Point was also failing to handle 90% of calls presented prior to the introduction of the contact centre application in 2022. We asked whether consideration had been given to revising the KPI, but managers were keen to maintain it as a standard they should be working towards.

63. If KPI 1 was based on calls handled as a proportion of the total volume of calls rather than the calls presented, operators would have handled 41% of all calls made between October 2023 and September 2024.

64. In relation to KPI 2, data is not readily available to help Enquiry Point accurately and routinely monitor whether it is answering 80% of enquiries at first point of contact.

65. Data is available on the proportion of calls that it successfully transferred to other teams within COPFS. This is generally around 10% of the calls it handles. While this can be a useful proxy for KPI 2, it does not account for other ways enquiries can be managed and does not take into account email enquiries. For example, following a failed attempt to transfer a caller to another team, operators may send that team an email or suggest that the caller does so. While the operator’s involvement in the enquiry will have ended at this stage, the enquiry may not be ‘answered’ from the caller’s perspective. Current systems do not allow for these actions to be recorded in a way that would allow robust data to be gathered.

66. The data from our own audit (paragraphs 80 and 83) suggests that Enquiry Point may not be meeting KPI 2, but much depends on how KPI 2 is to be interpreted.

67. The operator targets were described to us as more of a guideline. It was recognised that their performance each day and their call management would depend on the individual circumstances of each call they received. Operators we interviewed were aware of these targets but did not feel under pressure to ensure they met them every day. They felt there was good understanding among managers of issues that can affect daily performance, and they were clear that their focus should be the quality of call handling rather than the quantity. Nonetheless, the existence of the targets provided operators with a guide as to what was expected of them, and managers could monitor the targets to identify outliers and to explore variations in performance.

68. The data available from Enquiry Point was not sufficiently detailed to allow us to calculate the exact number of calls handled per operator per day. Experienced operators told us it was possible to meet and exceed the target of 40 calls per day. Much depended on the nature of the calls received, and whether they had managed any particularly complex or protracted calls.

69. In relation to the second target for operators, regarding hold time, data shows that 69% of callers were put on hold while their call was being handled. Between October 2023 and September 2024, the average time callers spent on hold was just over three minutes. This shows that operators are generally meeting this target. However, each month, the longest time on hold is noted. This was at least 16 minutes every month. The longest time on hold across the year was just over 24 minutes. Long hold times are usually caused by operators having difficulty transferring the caller to other COPFS teams, or having to wait on the call while the other team provides the operator with the information needed, rather than speaking directly to the caller. In our own call audit, there was an example of a caller hanging up after they had been on hold for 10 minutes.

70. The indicators and targets set out above are for internal use only. COPFS does not routinely publish any data about the Enquiry Point service, nor has it published any commitments about the service the public should expect to receive from Enquiry Point until very recently. In its Business Plan 2024-25, COPFS stated that it would respond to all calls and messages to Enquiry Point via initial contact or by returned call in four hours, providing all callers with a direct point of contact.[14] We welcome this ambitious goal, but found limited information about how it would be achieved or measured.

71. The data shows that Enquiry Point is not meeting the demand for its service. Between October 2023 and September 2024, 65,669 (19%) calls made to Enquiry Point were not admitted to the call queue. Of those admitted to the queue, 138,418 (50%) were abandoned. While many of these callers may try to call again another time or send an email instead, others may not.

72. The extent to which demand is met can fluctuate significantly month to month. It is susceptible not only to staffing and system issues noted at paragraph 44, but also to the prolonged call handling times caused by difficulties transferring callers to other teams and to the decreased availability of operators as they deal with significant failure demand.[15]

73. There is a need to look afresh at Enquiry Point’s demand, to consider what level of service COPFS aims to provide to those who call and email, set measurable targets that support delivery and to ensure Enquiry Point is appropriately staffed and supported by the wider organisation. Given public sector financial constraints, it cannot be expected that operators immediately answer every call made, but COPFS requires to consider whether it is striking the appropriate balance of resourcing and service delivery. These issues are explored further throughout the remainder of this report.

74. For those whose calls are answered by an operator, the results of our contact audit are generally more positive.

Contact audit results

75. By auditing calls and emails received by Enquiry Point, we sought to assess how well enquiries were responded to by COPFS. We assessed this using a range of measures.

76. In 96% of the enquiries we audited, we assessed the Enquiry Point operator’s response to be polite, respectful, professional and empathetic. We observed examples of operators being reassuring and patient with those who were anxious, and examples of operators remaining polite and professional with those who became angry and abusive. In the small number of enquiries where this was not the case, we considered the operator was not sufficiently empathetic given the subject matter of the enquiry, sounded disinterested in the caller’s issue, or provided an overly brief response to an email enquiry.

77. We also observed operators to be polite and professional when transferring enquiries to their colleagues in other teams across COPFS.

78. Where operators were required to provide information to the person making the enquiry, we assessed whether the information was supplied in accordance with COPFS policy and whether the information was accurate:

- information was supplied in accordance with COPFS policy in 86% of enquiries

- accurate information was supplied in response to 85% of enquiries.

79. There was some overlap in the errors identified when assessing these two measures. Where information was not shared in accordance with policy, this was because the information should not have been shared at all or too much information was shared; the information was incorrect or involved speculation on the part of the operator; or the operator was not qualified to provide the information because they were not legally trained. Examples of supplying inaccurate information included operators showing a lack of knowledge or understanding of justice processes, or not interpreting information on systems correctly.

80. We also considered how operators ‘disposed of’ enquiries and whether this was appropriate. We assessed this separately for call and email enquiries as the disposal options varied. Of the call enquiries:

- operators entirely resolved 45% of enquiries with no further action needed

- operators resolved a further 7% of enquiries after consulting with another COPFS team

- operators told 18% of callers to write to COPFS

- operators sent an email about 16% of enquiries to another COPFS team (for almost half of these enquiries, an email was only sent after the operator had tried to transfer the caller to another COPFS team but received no response)

- operators successfully transferred 10% of callers to another COPFS team

- 3% of enquiries were dealt with in some other way.[16]

81. We assessed that 84% of call enquiries were disposed of appropriately. We considered an alternate disposal may have been more appropriate for the remainder. For example:

- a caller seeking information about the status of their case was highly concerned about their child who was a witness. The operator provided an update about the case but given the caller’s concerns, it would have been more appropriate to also transfer the caller to VIA

- a caller provided information about another person who may have been responsible for an assault and details of additional injuries. This information should have been passed to a legal member of staff to instruct further enquiries and to consider disclosure and evidential implications

- a caller who asked whether a fiscal fine was a conviction was advised to make a subject access request to COPFS. This enquiry should have been resolved by the operator.

82. In some cases, it was another member of staff within COPFS rather than the Enquiry Point operator who was responsible for the enquiry not being disposed of in the most appropriate way. For example, an operator attempted to transfer a caller with an enquiry about special measures in a domestic abuse case to VIA, but VIA refused to take the call. Instead, VIA insisted that the operator wait while the information was found and that it was the operator who relayed the information to the caller, rather than VIA.

83. Of the email enquiries we audited:

- operators resolved 55% with no further action needed

- operators resolved a further 4% after consulting with another COPFS team

- operators forwarded 37% to another COPFS team to resolve

- operators responded to 2% by seeking to verify the emailer’s identity (no trace of any further emails could be found)

- no response to 2% of email enquiries could be found.

84. We assessed that 86% of email enquiries were disposed of appropriately. Examples of email enquiries that were not disposed of correctly included an enquiry that was forwarded to the wrong local office and emails that contained information which should have been recorded on COPFS systems but was not. While the majority of email enquiries were disposed of appropriately, many of these were routine enquiries from those working in the justice system such as the police or defence. Email enquiries from members of the public requiring a more tailored response appeared more likely to be passed on to other teams in COPFS for action, rather than the operator resolving the enquiry at first point of contact (as they would have done for a call enquiry).

85. Finally, we assessed the overall quality of enquiry handling by Enquiry Point, taking account of the issues listed above for each enquiry audited. We assessed the response as either good, reasonable or unsatisfactory. The overall quality of enquiry handling was:

- good for 67% of enquiries

- reasonable for 18% of enquiries

- unsatisfactory for 15% of enquiries.

86. Where enquiry handling was good, this was because the operator was polite, respectful, empathetic, reassuring and listened well. The operator verified the enquirer’s identity where relevant and provided accurate information. The operator either resolved the enquiry at the first point of contact or passed the enquiry to an appropriate person within COPFS for resolution. Where enquiry handling was reasonable, most of these features were present, but there was scope for improvement in some aspects of how the enquiry was dealt with.

87. Examples of unsatisfactory enquiry handling included:

- a domestic abuse victim who called wishing to have the charges against her partner dropped. The caller became distressed during the call and mentioned she was feeling suicidal. The operator was not empathetic and the victim was not referred or escalated to VIA but simply told to write to COPFS with her views about the charges

- after her initial enquiry was dealt with, a caller wished further information about what would happen when she arrived at court as a witness. Inaccurate information was given by the operator about the court process

- an email from a witness in a solemn case advising that they were unfit for court was not shared with the sheriff and jury team managing the case. As a result, that team did not become aware there was an issue until several months later.

88. Where Enquiry Point operators transferred calls or sent or forwarded emails to another team within COPFS for action, we also assessed the quality of subsequent call handling by that team. We found this to be:

- good for 45% of enquiries

- reasonable for 20% of enquiries

- unsatisfactory for 35% of enquiries.

89. Recurring issues in enquiries that had been passed to other teams and that were assessed as reasonable or unsatisfactory included no record of any action being taken to address the enquiry, delays in action being taken in response to the enquiry, and important information from enquiries not being added to case management systems. For example, a witness emailed Enquiry Point seeking clarification on whether she was needed at court. The operator forwarded the email to the local office to respond. There was no record of a response by the local office and the email enquiry was not imported to the case file. Ultimately, the witness attended court only to be told she was not required.

90. We found the overall quality of enquiry handling by Enquiry Point is good or reasonable for 85% of the call and email enquiries we audited. This is positive. We consider that the quality of enquiry handling could be improved even further if operators are supported by better guidance and training and if the other issues outlined in this report are addressed.

91. Comparing the results at paragraph 85 to paragraph 88, it is apparent that when enquiries are passed by operators to other teams within COPFS for resolution, the quality of enquiry handling drops. COPFS therefore needs to consider what more can be done to support staff across the organisation to respond to enquiries effectively and efficiently.

Email enquiries – initial response times

92. Those emailing Enquiry Point receive an automated acknowledgement of their email, advising that their enquiry will be responded to within three working days. While managers check the Enquiry Point mailbox to gauge progress in responding to emails, the current email system does not allow compliance with the response time to be easily monitored. However, we assessed the timeliness of the first response to the 56 email enquiries we audited. For two, no response could be found. For the remaining 54 enquiries, the average time to respond was 2.5 working days. Response times ranged from the same day to 10 working days. Emails from members of the public were likely to get a quicker response – 100% of their enquiries received an initial response within three working days, compared to only 54% of enquiries from professionals and partner organisations.

93. While we welcome the attention given to email enquiries from members of the public, the wide range of initial response times suggests more consistency is needed in how Enquiry Point responds to emails. No doubt some enquirers who do not receive a response within three working days as advised by the automated acknowledgement will re-contact Enquiry Point or another team within COPFS, thereby contributing to failure demand. Moreover, the three-day response time is not publicised and is not known to enquirers until they send their email. If this was publicised by COPFS (for example, on its website), those making enquiries could make a more informed choice about whether to email or phone.

Quality assurance

94. Enquiry Point itself had recently begun to monitor the quality of its enquiry handling shortly before our inspection. In April 2024, it commenced routine quality assurance of calls. This involves two calls per operator being quality assured each week. The calls are assessed based on the empathy shown by the operator, their professionalism and knowledge, how long they take to wrap up the call, and the action they take. Feedback, including good practice and areas for improvement, is provided to staff. Additional training can be provided to individuals if needed or, if common themes arise, training can be provided to all operators.

95. We welcome the introduction of quality assurance by Enquiry Point. It appears that it is being carried out in a constructive manner with a focus on learning and improvement rather than blame. We consider this approach should support further improvements in the already good service offered by operators.

96. We consider there are key ways in which the approach to quality assurance could be strengthened:

- lengthy calls were not being quality assured at the time of our inspection due to a lack of capacity. We consider lengthy calls may be a particularly good source of learning

- quality assurance is focused on how calls are dealt with by Enquiry Point. Consideration could be given to extending this to how enquiries are resolved, regardless of whether the enquiry is concluded by an operator or passed on to other teams within COPFS

- there is a need to quality assure responses to email enquiries.

97. As we were preparing this report, we heard that Enquiry Point’s quality assurance capability is being strengthened and that consideration is now being given to monitoring email responses, which we welcome. We also consider that there is scope for those carrying out quality assurance to identify calls that should be used to support the training of new operators.

98. In addition to the more formal quality assurance activity, we heard that Enquiry Point managers frequently listen in to calls and provide feedback to staff.

User satisfaction

99. In its service improvement strategy, COPFS sets several outcomes that it aims to achieve, one of which includes seeking ‘continuous improvement through user feedback’.[17] We welcome this intention. However, as yet, there is no mechanism in place by which COPFS regularly seeks and acts on feedback from those who have called or emailed Enquiry Point.

100. We heard that some ad hoc attempts to gather user feedback had taken place in the past. This has included operators asking callers at the conclusion of their call whether they were satisfied with the service. This took place during an annual Customer Service Week. The results do not appear to have been analysed or shared widely, and we heard little about how they had been used to improve or develop the service.

101. Other justice agencies routinely carry out customer satisfaction surveys. Both SCTS and Police Scotland commission external agencies to assist with this process. SCTS measures court user satisfaction, while Police Scotland carries out monthly user experience surveys.

102. In a contact centre environment such as Enquiry Point, customer satisfaction surveys should be carried out routinely. The results should be used to inform training and service improvements as well as positive feedback for staff (see Recommendation 5).

103. Given the absence of user satisfaction data to help us assess the quality of the service provided to those making enquiries, we carried out our own survey. Key findings were that:

- 65% of respondents were satisfied with how polite and professional the person who dealt with their enquiry was

- 49% were satisfied with the knowledge of the person who dealt with their enquiry

- 36% of respondents were satisfied with how quickly they received a response.

104. When we asked respondents to rate their satisfaction with their overall experience of contacting Enquiry Point:

- 38% were satisfied

- 45% were dissatisfied

- 17% said they were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

105. Despite our survey being open for less than three weeks and attracting only 85 responses, the quantitative and qualitative results provide useful feedback for a service to consider and use to make improvements. When we asked respondents what could improve in how COPFS responds to enquiries, the most common theme was the need to improve the speed with which enquiries are managed. Many respondents complained of long call waiting times. Some respondents felt they received a prompt response from Enquiry Point itself, but noted delayed responses if their enquiry was transferred to another team within COPFS. This highlights that the internal challenges faced by operators in making contact with other teams and the failure of other teams to deal with emails promptly are visible to service users.

‘They should respond faster, and the waiting times on the phone line require to be cut down drastically, as these are very, very high.’ (Solicitor survey respondent)

‘I default to emailing COPFS as calling is usually not practical, more often than not I have called and the line is not accepting calls. It is not a method of contact I would rely on.’ (Victim/witness support organisation)

‘Email responses are great, quick and helpful. Always feel my enquiry is treated with urgency and respect.’ (Victim/witness support organisation)

Complaints

106. Monitoring complaints is another means of gathering feedback about a service. COPFS may receive complaints specifically about the service provided by Enquiry Point, or where the role played by Enquiry Point is one feature of a complaint about its service more broadly. We asked for data about complaints involving Enquiry Point. This was not available as complaints are not categorised in such a way as to make those involving Enquiry Point easily identifiable. The inspectorate highlighted this as an issue in our 2013 review of Enquiry Point.[18] Our recommendation that it be addressed remains outstanding.

107. While no data was available, complaints involving Enquiry Point are shared with the service’s business manager who plays a role in investigating the complaint and providing a response. So long as all relevant complaints are brought to the business manager’s attention, there is an opportunity for learning to be gathered and acted upon. The lack of robust data, however, means opportunities to monitor trends in complaints are lost.

Overall assessment

108. Evidence gathered during our inspection shows that the quality of enquiry handling by Enquiry Point is generally good. There is some scope for improvement, particularly in how enquiries are managed when assistance is needed from other teams within COPFS. The ease and speed with which those making call enquiries can access operators is of concern, as is the timeliness of responses to email enquiries.