Related Downloads

Related Links

Additional

Part 2: Off duty criminal allegations against the police

261. While our inspection mainly focused on how COPFS manages criminal allegations made against the police while they are on duty, we also considered how off duty allegations are handled. This was because the boundary between on and off duty behaviour can sometimes be blurred, and because of the high level of public interest in, and need for reassurance about, how all criminal complaints against the police are managed.

262. Off duty criminal allegations are managed by COPFS in a way which is more akin to the process for managing allegations of criminality against any member of the public. Off duty criminal cases are only reported to COPFS where there is a sufficiency of evidence to establish that a crime has been committed and that the accused is the perpetrator. Once reported, there are some bespoke processes for handling off duty cases which are discussed further below.

Case review

263. We reviewed 40 cases in which criminal allegations were made against the police while they were off duty to help us understand how such cases are managed by COPFS.

264. We sought to select cases that had been reported to COPFS between 1 April 2019 and 30 September 2020. As with our on duty case review, the cases would be drawn from this period in an effort to strike a balance between recently reported cases, and cases where sufficient time had passed that we could assess how they had been progressed. We experienced challenges in identifying off duty cases, but ultimately selected our sample from three sources.

265. We initially requested data from COPFS on all cases which had been reported to it involving off duty police officers or staff during the relevant period. Unfortunately, this data was not available. We then sought Police Scotland's assistance. Police Scotland was able to provide us with the number of off duty allegations made against the police. However, because there may be multiple allegations in each case, this did not correspond with the number of cases reported to COPFS.[59] We also asked Police Scotland for the COPFS reference numbers for off duty allegations so that we might identify the cases on COPFS systems. Police Scotland provided a list of 34 reference numbers, but it was clear from the low number that this list was incomplete.

266. We then carried out our own search of the COPFS case management system to identify cases involving the police. Generally, crime reports are submitted to COPFS by way of a Standard Police Report (SPR). This report has an occupation field in the 'Accused's Details' section which can be completed by the reporting officer selecting from a pre-set list of occupations. In this field, where the accused is a police officer or police staff, reporting officers should select the option 'Local Government (Police)'. This is not particularly instinctive, and a secondary data field is frequently used instead. This is a free text field, and reporting officers use a variety of terms to describe police occupations. We carried out a search of these two occupation fields to identify all cases where the accused was an officer or member of staff working for any police service in Scotland. This yielded 53 cases. Again, we could not be confident that this was a complete list of cases because the reporting officer may have selected other data fields or entered a term for which we did not search, or the occupation fields may simply have been left blank.

267. We also became aware of a spreadsheet maintained by staff within the National Initial Case Processing (NICP) team which listed 112 off duty cases of which they were aware and which were reported during 2019 and 2020 (although it was not immediately clear how many of these were within our sample period). This helped us to identify additional cases, but again was not a full list of all off duty criminal complaints.

268. We compiled a list of cases drawn from the three sources, eliminated duplicates and randomly selected 40 cases for review.

Off duty case review cohort

269. In the 40 cases we reviewed, the accused was male in 33 (83%) and female in seven (18%).[60] Thirty-six (90%) cases involved those working for Police Scotland, and four (10%) cases involved those working for British Transport Police or the Ministry of Defence Police. In 39 (98%) cases, the accused was a police officer, and in one case, the accused was a member of police staff. Of the 39 police officers who were accused, their rank was identified in only 25 cases. In the remaining 14 cases, it was unclear from the SPR or any other case documentation what the accused's rank was. Where the rank was specified, it ranged from police constable to chief inspector.

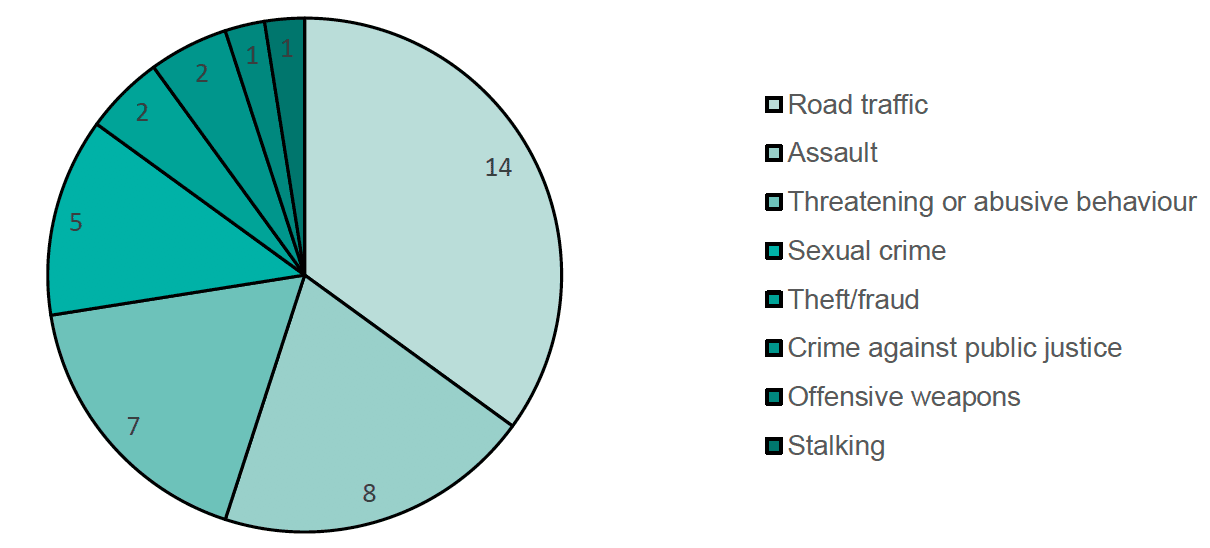

270. The off duty allegations covered a range of criminal offending from minor road traffic offences to serious sexual offences. In 27 (68%) cases, there was a single charge against the accused, while 13 (33%) cases included multiple charges. Chart 6 shows the main offence in each of the 40 cases. For the cases with multiple charges, we deemed the main offence to be the one that would result in the most severe penalty.

271. In at least 12 (30%) of the 40 cases there was an indication that at least one of the offences featured a domestic element.

Definition of on and off duty allegations

272. While we sought to review 40 off duty criminal complaints, it would be more accurate to say we reviewed 40 cases that were subject to the process for off duty complaints. This is because we found that 10 (25%) of the cases should have been dealt with as on duty criminal complaints and reported to CAAP-D. In each of these 10 cases, errors were made both by the police service in using the wrong route to report the cases to COPFS, and by COPFS itself in not identifying the cases as on duty and re-routing them to CAAP-D.

273. The lack of a mutually agreed and well understood definition of on and off duty offending among all those dealing with criminal allegations against the police contributed to these errors. Within COPFS, there is no up to date, easily available written definition of on and off duty offending. This is linked to the lack of written policy and guidance noted at paragraph 120. The Lord Advocate's Guidelines on the investigation of complaints against the police from 2002, which appear to be obsolete and are no longer available to COPFS staff, had stated that 'offences committed by an officer or employee whilst 'off duty' should be reported to the District Fiscal in the usual manner, except where the conduct involves an allegation of corruption, or use of the officer's position as a police officer.' We could find no up-to-date articulation of the distinction between on and off duty to which COPFS staff could refer.

274. In contrast, Police Scotland has sought to define on and off duty complaints. Its standard operating procedure on complaints about the police states that a police officer is on duty when:

- operating within duty hours

- when off duty and they identify themselves as an officer verbally or by producing their warrant card and uses, or attempts to use, police powers to deal with a situation where it may be inferred they would be in neglect of duty had they not acted. In essence, by their actions, they return to an on duty capacity.

275. It also states that a member of police staff is only on duty when they are operating within duty hours.[61]

276. It is clear from Police Scotland's definition and from the outdated 2002 guidelines as well as current practice we observed in CAAP-D that on duty offending is not confined to when a police officer is at work. Depending on the circumstances, officers' conduct while they are off duty may be treated as if they were on duty. In addition to incidents where an off duty officer has placed themselves on duty by their conduct, CAAP-D has over the years widened its remit by specifying certain types of offences which should be reported to it, regardless of whether they have been committed on or off duty. In correspondence from 2015 to the Chief Constable of Police Scotland and PIRC, CAAP-D noted that any instances of corruption, perjury or sexual offences by officers both on and off duty be referred to CAAP-D. More recent correspondence has suggested that it is only more serious sexual offences that should be referred to CAAP-D.

277. This expansion of the CAAP-D remit is not recorded in any COPFS guidance or policy which is available to all staff. Yet those staff handling off duty complaints need to be aware of it, so that they might divert to CAAP-D any cases which have been wrongly reported by the police using the off duty process. Moreover, it was not clear to us that the policy changes in the correspondence to Police Scotland were communicated to other police services operating in Scotland. It was also not clear that the policy changes were widely known within Police Scotland itself given that it was responsible for reporting serious sexual offences to COPFS using the off duty process.

278. From our case review and from our interviews with staff in COPFS, there is a lack of clarity around the definition of off and on duty criminal conduct. In our case review, we considered that 10 off duty cases should have followed the process for on duty criminal complaints and been referred to CAAP-D either because the cases involved criminal conduct that was clearly committed on duty, the officer had placed themselves on duty during the incident, the conduct was linked to the accused's role as a police officer, or the off duty conduct was of a type that should have been referred to CAAP-D. In some cases, we believed the conduct to have been clearly on duty, whereas others were more finely balanced and advice should have been sought from CAAP-D on how they should be managed. Examples of cases that we believe were wrongly subject to the process for handling off duty criminal complaints included:

- four cases in which the officers committed road traffic offences while driving a police vehicle and where it appeared they were on duty

- a case where an officer, while off duty, became involved in an incident, declared himself to be a police officer and restrained a member of the public

- a case where an officer sent indecent messages while on duty and from within a police station (some messages were sent while he was off duty)

- a case in which an officer met a vulnerable complainer and obtained her contact details through his policing role albeit that the offences were committed off duty (we are aware of a similar case being treated as an on duty criminal complaint and being dealt with by CAAP-D)

- cases in which sexual offences, some of which were serious sexual offences, were committed by officers off duty, but which should have been reported to CAAP-D under the policy noted at paragraph 276. In one of these cases in particular, the circumstances may have merited an independent investigation by PIRC overseen by CAAP-D.

279. In the cases outlined above, generally no consideration appeared to have been given to whether the criminal conduct was on duty and to consulting CAAP-D for advice. In contrast, we reviewed other cases where there was uncertainty about whether the conduct was on or off duty but we saw good engagement with CAAP-D who provided appropriate advice about how the case should be managed. In particular, there appeared to be confusion about whether an officer is on duty while travelling to and from work. While the Head of CAAP-D and most of the unit's staff were clear that a commuting officer is off duty, other staff were less sure.

280. As noted above, it is a matter of policy that on duty officers are only prosecuted on the instruction of a Law Officer. Where cases are wrongly categorised as being off duty, decisions to prosecute are being made without the robust scrutiny to which they should be subject and often by junior members of staff. It is therefore important that cases are categorised appropriately and subject to the correct process. Guidance, supported by efforts to raise awareness of its contents, should be provided to the police and to staff in COPFS to ensure this occurs. They should also be encouraged to seek advice from CAAP-D if there is any uncertainty.

Recommendation 15

COPFS should provide written guidance to its staff and to reporting agencies covering the definition of on and off duty criminal allegations against the police. COPFS should also work with reporting agencies to ensure they submit on and off duty cases via the correct route.

281. One issue we considered during our inspection is whether off duty cases should be subject to the same process as on duty cases and be reported to and assessed by CAAP-D. We consider that this is not necessary. On duty cases are dealt with differently in recognition of the privileged place that the police occupy in society and the powers they exercise on behalf of the state. The current reporting arrangements for off duty cases are appropriate, albeit that there is scope for improvement in how they operate. We believe off duty officers and staff are entitled to be treated as any other members of the public. Where their behaviour while off duty reflects badly on the policing service, then that is for the police to consider via disciplinary or misconduct proceedings rather than COPFS. Having criminal conduct which is genuinely off duty and unconnected to the accused's role with the police dealt with by those in COPFS who have everyday experience and expertise in marking cases involving members of the public is beneficial and should achieve consistency in decision making.

282. However, maintaining separate processes for on and off duty criminal complaints against the police is dependent on the police and COPFS ensuring that on and off duty cases are appropriately distinguished and the correct process used. In her review of police complaints handling, Dame Elish Angiolini suggested there may be merit in reporting off duty criminal complaints to CAAP-D, as well as to the local Procurator Fiscal.[62] We do not consider that dual reporting is necessary, but we do agree with Dame Elish Angiolini that there is a need for strategic oversight of both on and off duty complaints and more dialogue between those responsible for each process. It is not acceptable that a quarter of cases in our off duty sample were managed via the wrong process. If the recommendations and suggestions in this report for improving the management of off duty cases are not implemented effectively, then Dame Elish Angiolini's suggestion of dual reporting, or even the possibility of reporting all criminal cases against the police to CAAP-D, should be revisited.

Recommendation 16

COPFS should ensure that there is strategic oversight of how on and off duty criminal allegations against the police are managed, and greater dialogue between those responsible for handling each type of allegation.

Reporting off duty allegations to COPFS

283. As noted at paragraph 265, COPFS cannot identify from its systems how many off duty criminal complaints are made against the police. This is because the occupation field on the SPR submitted by the police to COPFS is not consistently filled out across police services operating in Scotland and even within Police Scotland. Sometimes the occupation field may be left blank and it is not clear at all from the SPR that the accused is serving with the police. Having a more consistent approach would have two main benefits: firstly, it would allow COPFS to gather data on off duty criminal complaints and make it easier to identify and have oversight of all such cases; and secondly, in each case, it would help ensure that the person dealing with it knows the accused is serving with the police. To ensure a more consistent approach, COPFS should instruct reporting agencies on how to complete SPRs with the correct occupation data. This could be supported by adding a new option to the current list of occupations that is easier to find (for example, by replacing 'Local Government (Police)' with 'Police'.

Recommendation 17

COPFS should provide guidance to the police on ensuring that SPRs are completed with the correct occupation information.

284. When we spoke to staff marking off duty criminal complaints, we heard about other ways in which SPRs could be improved. For example, they told us they often require to request the full statements from the reporting officer as the SPR does not furnish sufficient information. They were surprised that reporting officers did not ensure that an SPR relating to one of their colleagues was of a better quality. In our case review, we found that 19 of the 40 (48%) cases involved requests for further enquiries to be carried out before a final marking could be applied, and 12 of those cases included a request for full statements.

285. We also heard that SPRs can sometimes lack detail about the accused and their status. In all 39 cases we reviewed where the accused was a police officer, reference was made to their job in the 'Accused's Details' section of the SPR. However, we heard that prosecutors may not check that section when marking the case and they may be unaware the accused is an officer unless it is mentioned elsewhere in the report. In six (15%) cases we reviewed, there was no mention in the main body of the SPR that the accused was serving with the police. Also, in only six (15%) cases was any information provided about whether the accused had been suspended or placed on restricted duties.

286. We also found that the information provided about the background and personal circumstances of the accused varied across reports. In some, almost no information was provided whereas others provided full information about the family and personal circumstances that were affecting the officer at the time of the offence. While some stakeholders we interviewed suggested there may be a reluctance for personal information to be included in SPRs, such information helps prosecutors make more appropriate decisions taking into account all the circumstances of the case. For example, one case we reviewed referred to the complex family background of the accused officer, prompting the prosecutor to request further information. Once received, the information caused the prosecutor to divert the accused from prosecution which was a more appropriate outcome.

287. The quality of SPRs, regardless of the identity of the accused, has been a recurring theme in our previous inspection reports. We intend to explore this issue further in our future inspection programme.

Decision making

288. COPFS applies prosecution policies and Case Marking Instructions (CMIs) to the individual circumstances of each case in order to ensure consistency in decision making. Nonetheless, some stakeholders we interviewed perceived that off duty police officers are treated more harshly by COPFS than other members of the public. COPFS staff also seemed to hold varying views on off duty cases – some believed the accused should be treated exactly the same as any member of the public, while others appeared to suggest that those serving with the police may be held to a higher standard, essentially because they should 'know better'. In seven of the 40 (18%) cases we reviewed, we noted that charges were changed, CMIs not followed, or forums changed without explanation. These actions by prosecutors effectively increased the severity of the charge or potential sentencing options when other, less severe alternatives were available and would have been a reasonable action to take. While the action taken may have been reasonable, the lack of a recorded rationale made it difficult to understand or justify. On the other hand, we also reviewed one case where court proceedings should have been initiated due to the severity of the charge however a fixed penalty was offered and accepted instead.

289. More positively, we found evidence of COPFS appropriately reassessing cases at various stages based on new information that had come to light. For example, in three cases, no action was taken after COPFS had initially marked further enquiries and in five cases, COPFS decided to take no further action at a point after proceedings had been initiated.

Decision making process

290. During our inspection, we heard that all SPRs involving off duty criminal allegations against the police should be submitted to NICP. NICP either marks the case itself or refers it to the local sheriff and jury team or a specialist unit. Upon submitting the SPR to NICP, the police should send an email with the case details to the 'NICP off duty mailbox'. This alerts NICP to the case and a bespoke process should follow. This includes all off duty cases being logged on a spreadsheet. Alerting NICP to the cases is important because, as noted above, off duty cases are not always easily identifiable and, without the notification process, there is a risk that the cases will not be recorded on the log. Of the 40 cases we reviewed, there was no evidence in the case record of 29 (73%) cases that the police had alerted NICP to the existence of the case. However, only 14 of the 40 (35%) cases were not logged. This suggests that either the police did notify NICP but the notification was not imported into the case record, or that NICP or other COPFS staff are adding cases to the log as and when they come across them. Despite this, given that just over a third of cases were not logged, it is clear that current processes are not sufficiently effective so as to identify all off duty cases. If Recommendation 17 were to be implemented and the police were to complete SPRs consistently with the correct occupation information, this could provide an additional means of NICP being able to identify and record all off duty criminal cases where the accused is serving with the police.

291. The responsibility for marking off duty criminal complaints lies primarily with NICP. NICP marks all summary level custody, report and one-day undertaking cases. The marking of other undertaking cases is usually carried out by local court teams but, where the case involves an off duty allegation against someone serving with the police, it should be marked by NICP. In our case review however, we found that only 28 out of the 40 (70%) cases were marked by NICP. While three petition custody cases were appropriately marked by other teams, nine summary level undertaking cases which should have been marked by NICP were marked by local court teams. In these cases, it appears that the NICP process was bypassed. Local court staff have recently been reminded by email that all off duty cases should be referred to NICP, although it would be helpful if the approach to dealing with off duty cases was set out in guidance that is easily available to all staff. When marking is more widely distributed among COPFS staff, it can result in errors by those who are less familiar with the latest case marking instructions and processes.

292. The process by which the off duty cases in our review were marked appeared to have an impact on how quickly decisions were taken. In the 28 cases marked by NICP, 46% were marked within 28 days. In the 12 marked by local court, 83% were marked within 28 days. While marking appeared to be faster in local court, NICP staff generally delayed their decision pending the receipt of further information. We reviewed two almost identical cases in which domestic offences were alleged to have been committed. In both cases, there was information about the accused officer's mental health, and personal and family issues. In one case, NICP marked the case after five days. The marking decision was to defer a final decision until further background information was gathered. The information was provided and the final marking decision, taken 92 days after the initial decision, was that the accused be diverted from prosecution. In the second case, the marking decision was taken by local court on the same day the case was received. The marking decision was to prosecute the accused in the Sheriff Court, despite the existence of mitigation against initiating court proceedings.

293. When cases are marked by NICP, they should follow a bespoke process. An off duty process map drawn up in 2015 and available on the intranet sets out the process. It describes how the police refer the cases to NICP, who should mark the case and the timescales for marking. We noted an attempt by staff to follow the process map in one of the 40 cases we reviewed. More generally, however, we heard that staff are unaware of the process map, and the steps it describes are not being followed.

294. The process map requires, for example, a Principal or Senior Depute to mark off duty cases within seven days. Generally, the current practice is that off duty cases should be allocated to one of two dedicated Deputes who aim to mark the cases within 14 days. They retrieve the cases from a 'virtual tray' set aside for off duty cases. These Deputes are allocated time, alongside their usual duties, to deal with the cases.

295. One issue we have identified with the current practice is that cases are not always being allocated to the virtual tray set aside for off duty cases. This means they are not brought to the attention of and marked by the dedicated Deputes. In addition, staff in local court and in CAAP-D, who may have cause to re-allocate cases to this virtual tray were not always aware of it. In one case we reviewed, an SPR relating to off duty criminality was submitted to CAAP-D in error. CAAP-D attempted to transfer the case the next day, but sent it to a local court tray. It was not re-transferred to the correct off duty tray until eight months later which significantly delayed the subsequent prosecution.

296. Senior staff in NICP are aware the process map is out of date and does not reflect current practice, and plans are underway to revise it. In doing so, we would encourage them to consult with CAAP-D and to include information on the need to confirm that the case relates to off duty criminal conduct and is not a case which should be subject to the process for on duty criminal complaints.

Decision making timescales

297. COPFS has a general target that a final marking decision should be made within 28 days in 75% of summary cases. Of the 40 cases we reviewed, 36 (90%) were given an initial marking decision within 28 days and 24 (60%) were given a final marking decision within 28 days (see Table 7).

| Timescale | Marked by NICP | Marked by local court | All cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Same day | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| 1 to 7 days | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| 8 to 14 days | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 15 to 28 days | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Within 28 days | 14 | 10 | 24 |

| 29 to 84 days (4 to 12 weeks) | 4 | - | 4 |

| 85 to 168 days (12 to 24 weeks) | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 169 to 252 days (24 to 36 weeks) | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| 253 to 365 days (36 to 52 weeks) | 2 | - | 2 |

| Over 52 weeks | 1 | - | 1 |

| Total | 28 | 12 | 40 |

298. In the cases where there was a substantial delay of 197 and 259 days, the initial and final marking decisions were made on the same day. In the case that took 197 days, there was no indication in the case records that COPFS was waiting for further information before a decision was made. The reason for the delay was not apparent or recorded. In the case that took 259 days to mark, the delay was caused by the case being transferred to the wrong virtual tray (see paragraph 295).

299. Only 14 of the 28 cases (50%) marked by NICP were given a final marking decision within 28 days (see Table 7). According to the off duty process that appears no longer to be in use, NICP should mark all cases within seven days. It is not clear whether this target is for initial or final marking. Regardless, only 15 (54%) of NICP cases were initially marked within seven days while 10 (36%) of NICP cases were finally marked within seven days. During our interviews, we heard that NICP currently tries to mark off duty cases within 14 days – 20 (71%) of NICP cases were initially marked within 14 days and 11 (39%) were finally marked within 14 days.

300. As noted above, delays in making a final marking decision can be caused by poor SPRs, or simply cases in which deputes require further information before reaching the most appropriate decision. While there will always be more complex cases that require further information, NICP could provide feedback to Police Scotland on how it can improve the information it provides so as to facilitate earlier decision making. It would be for Police Scotland to decide whether additional effort on its part, such as routinely submitting full statements with SPRs, is worthwhile in light of its desire for cases against the police to be resolved as quickly as possible.

301. When revising its off duty process map, NICP should clarify its target timescale for marking cases and be clear whether this target relates to initial or final marking. If it relates to initial marking, consideration could be given to also setting a target for final marking – if senior managers only monitor the timescales for initial marking, they may lose sight of how long it takes to reach final decisions. If the targets are to be more stretching than those it sets for cases where the accused is a member of the public, NICP should be clear about the rationale for this. Until now, the targets NICP has itself set for marking off duty cases are more challenging than for cases where the accused is not serving with the police. There is, presumably, a desire to expedite cases involving the police and a recognition that it is in the interests of policing and the criminal justice system more generally to resolve these cases as soon as possible. However, this must be weighed up against other cases that COPFS also wants to expedite, such as those involving vulnerable complainers.

Assessment of the off duty decision making process

302. Overall, we considered that the current, informal process for managing off duty criminal complaints, if it was properly followed in every case, is reasonable. While we are aware NICP has plans to revise its off duty process map, which we welcome, we think it may first be useful for NICP to consider the purpose of the off duty process, including why cases are allocated to designated deputes, why there are shorter timescales for marking and for what purpose it is maintaining a log of off duty cases. We do not disagree in principle with any of these aspects of the process and think there can be benefits to each, but while those we interviewed were keen to deliver the process, we were not confident there was a shared understanding of why a separate process existed. For example, while a log of off duty cases is maintained by NICP, awareness of it was very low and those we spoke to were not sure if and how its contents were used. To avoid staff doing unnecessary work, NICP should consider what it is trying to achieve in the management of off duty cases, and then ensure its processes support that goal and are consistently delivered. We consider, for example, that having dedicated staff working on off duty cases helps maintain a consistent approach and facilitates liaison with CAAP-D and with the police. Having a log of off duty cases can support oversight of all criminal allegations against the police and communication with the police particularly on the status and progress of cases. This will only be achieved however, if there is good awareness of the off duty processes and if they are implemented consistently in all cases.

Recommendation 18

COPFS should clarify the purpose of its approach to off duty criminal complaints against the police and design a process for handling such cases that supports that purpose. All relevant staff should be made aware of the process and it should be followed in all off duty cases.

Prosecuting off duty criminal cases

303. Once a decision has been made to initiate court proceedings in an off duty criminal case, the case is transferred to local court teams for prosecution. Off duty cases are usually marked to be treated as Advance Notice Trials. This means that the case should be allocated to a specific depute who should be given sufficient time, having regard to the complexity of the case, to prepare the case thoroughly. Without being treated as an Advance Notice Trial, significant time may pass before the case is reviewed for the intermediate diet shortly before the trial. Some cases are marked as Advance Notice Trials because they include a child witness or because they relate to a sexual crime. However, in some cases, the mere fact the accused is a police officer is the reason why advanced preparation is required. There are several reasons why this may be the case, including:

- there being a possible conflict of interest, particularly in smaller sheriffdoms, where the accused is well-known to COPFS staff and even sheriffs

- the high profile nature of the case and likelihood of significant media interest

- the fact that cases against officers are often vigorously defended, with extensive defence preparation, investigations and the use of experts which would not be the norm for similar cases not involving the police. Because of this, the trials can be longer than expected. For example, one of the cases we reviewed relating to an assault that was captured on CCTV resulted in five days of evidence, including expert testimony.

304. It will not always be clear to local court teams however why the case has been marked as an Advance Notice Trial. The deputes in NICP who mark the majority of off duty cases may wish to consider providing more detailed guidance for local court staff on the reason advanced preparation is needed. Consideration could be given to the local CAAP champions recommended above for on duty cases (per Recommendation 12), also having oversight of off duty cases as both share similar challenges, such as the need for additional preparation. The champions could build up expertise in cases involving the police, acting as a regular point of contact and establishing relationships with the police and the small number of defence agents who tend act in both on and off duty cases.

305. While additional preparation is often thought to be required for off duty cases, we found no evidence in our case review that such cases are expedited solely because the accused is serving with the police. In the cases we reviewed that were expedited, this was due to the nature of the case or the involvement of vulnerable witnesses. While the police and all those involved in the off duty cases will understandably want them to be resolved as soon as possible, as noted above, COPFS also requires to prioritise a range of other cases such as those involving child witnesses. If efforts are made to prioritise too many types of cases, there is a risk that none are, in fact, prioritised.

Off duty case review – outcomes

306. Table 8 shows the final marking decision in the 40 off duty cases that we reviewed, as well as the final outcome in each case:

- of the direct measures, six were fixed penalties, one was a fiscal fine and one was a compensation order. Three of the six fixed penalties were not paid, resulting in proceedings in the Justice of the Peace Court

- in one of the Justice of the Peace Court cases and two of the Sheriff summary cases, no further action was taken after proceedings were initiated. This generally occurs when new information comes to light that was not available at the time of final marking.

| Marking decision | Final marking decision (number of cases) | Final outcome (number of cases) |

|---|---|---|

| No action | 5 | 5 |

| No further action | n/a | 4 |

| Diversion from prosecution | 2 | 2 |

| Direct measures (fixed penalty/fiscal fine/compensation order) | 8 | 5 |

| Justice of the Peace Court | 8 | 9 |

| Sheriff Summary | 15 | 13 |

| Sheriff & Jury | 2 | 2 |

307. Of the 24 that proceeded to court, in 11 cases the accused pled guilty, the accused was found guilty in two cases, and in 11 cases the accused pled not guilty and the proceedings are ongoing. These ongoing trials will inevitably have been impacted by Covid-19 and the associated court closures and restrictions that began in March 2020.

| Forum | Pled guilty | Found guilty | Trial ongoing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Justice of the Peace Court | 8 | 0 | 1 |

| Sheriff Summary | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Sheriff & Jury | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 11 | 2 | 11 |

Communication with complainers

308. Of the 40 cases we reviewed, there were 16 (40%) in which a referral to VIA was appropriate for the complainer or a witness. Referrals were made in all those cases. In 14 of the 16 cases, we saw evidence of communication with either the complainer or a witness. It is the final marking decision which usually triggers a referral to VIA. However, VIA can sometimes be made aware of cases prior to the final marking (such as a custody case relating to a domestic offence where the marking has been deferred pending further information). In eight of the 14 cases, there was communication from VIA within seven days of the case being reported to COPFS. In a further two cases, there was communication within 28 days and in one other case it was 38 days.

309. In the remaining three cases where we saw evidence of communication with the complainer, we found a substantial delay in that communication. In these cases, the complainer was not contacted until after 121 days, 231 days and 266 days respectively. COPFS may wish to consider their communication strategy for informing complainers or vulnerable witnesses that a case has been received and is under consideration and to reassure complainers they will be notified of the final outcome.

310. We were concerned by the two cases where we found no evidence of any communication with the complainer at all. Both cases involved a domestic element and VIA referrals had been made. Both cases were eventually diverted from prosecution yet there appears to have been no communication of that decision to the complainer. In one of the cases, the complainer wrote to COPFS twice, but there is no record of any response. It is essential that the public have confidence in how criminal allegations against the police, even off duty, are managed and in prosecutors' use of diversion as an appropriate means of dealing with criminality. It is unclear whether there was simply a failure to communicate in these two cases or whether there is a broader issue with how COPFS communicates with complainers in cases where diversion is being considered. COPFS may wish to ensure that its approach to communicating with complainers in cases where the accused is being considered for or has completed diversion from prosecution is appropriate.

Communication with the accused

311. In Scotland, summary complaints are usually served on the accused person at their home address either by postal or personal service. Those serving with the police, along with those serving in the armed forces, appear to be the only professions where the employer is provided with information on charges and proceedings before the accused themselves. We heard that this approach was taken to protect the accused so their home address does not feature on a complaint which would be a matter of public record and which may be disclosed to the press. However, current (albeit dated) guidance for COPFS in the Book of Regulations states that, 'Where an incident has occurred outside the course of duty … an officer should be designed as at his or her home address unless there has been a specific request for designation at the place of work and the Procurator Fiscal considers that that request is reasonable.'[63]

312. We found that in practice, in the vast majority of off duty cases, reporting officers had listed the accused's disclosable or citation address as the Professional Standards Department without stating any reason and without Procurator Fiscal consideration. This practice led to problems in some of the cases we reviewed:

- in one case, there was failed service of the complaint and no proof of service either on PSD nor the accused resulting in the time bar being missed and no action being taken

- in one case, an accused required to be assessed for suitability for diversion but the only address in the SPR was for PSD. This led to delays in the appropriate social work department making direct contact with the accused

- in one case where COPFS sent the complaint to the accused care of PSD, despite being sent weeks in advance, PSD contacted COPFS two days prior to a pleading diet as they had 'just discovered the complaint' and a new complaint required to be drawn up. This process delayed the court proceedings for the accused by over six weeks

- in one case, COPFS staff changed the citation address of an officer from his home address to that of Police Scotland's PSD. The officer did not serve with Police Scotland however. The complaint was returned to COPFS by Police Scotland, but this error resulted in a six month delay between final marking and the correct service of the complaint.

313. While we understand the desire to keep the home addresses of those serving with the police confidential, COPFS should work with Professional Standards Departments to consider how to avoid the kinds of problems outlined above recurring.

314. Police services require regular updates on the progress of cases involving off duty criminal complaints against their officers. This is particularly important where the officers are suspended or on restricted duties. There is no one process by which a police service's PSD can seek updates. Depending on the status and progress of the case, updates may be provided by NICP or local court. The log of off duty cases maintained by NICP can help in this regard but, as noted above, it is not yet a comprehensive list of all cases and the information it contains is limited. We heard from the police that they can struggle to know where to go for updates and can be relayed around different offices and functions within COPFS. The difficulties in obtaining updates appeared to have led to an unusual step in one case we reviewed, whereby a PSD officer with no involvement in the case was added to the witness list in an apparent attempt to keep track of developments. Given that NICP is already attempting to maintain a log of all off duty cases, consideration should be given to ensuring that the log is more accurate and that the person who manages the log acts as a key point of contact for all PSD enquiries (or that access to the log is granted to another individual who can direct PSD as needed). Access to the log could also be provided to CAAP-D. This could act as an additional safeguard to allow CAAP-D to identify cases which may more appropriately be considered as on duty criminal allegations against the police.