Related Downloads

Related Links

Additional

6. Section 275 applications in the Sheriff Court

234. Our inspection focused almost entirely on the Crown's approach to managing section 275 applications in the High Court as this is where the majority of section 275 applications arise. However, data from SCTS suggests that between 2018-19 and 2020-21, 9% of section 275 applications were made in the Sheriff Court.[83] We have therefore given brief consideration to the Crown's approach to section 275 applications in the Sheriff Court and, in this chapter, highlight ways in which practice varies from that in High Court cases.

235. Our findings are based on interviews with staff working in the Crown's Local Court function (which manages sheriff solemn and sheriff summary cases), and a review of 11 cases heard in the Sheriff Court.

236. In Phase 3 of our case review, we sought to review Sheriff Court cases in which section 275 applications had been made. As noted elsewhere, COPFS systems did not allow for the easy identification of cases in which section 275 applications had been made. COPFS staff were therefore asked to notify us of relevant cases at sheriff and jury and summary levels between 1 January 2021 and 30 June 2021. Only 11 cases were identified. We are not confident that this was an accurate reflection of the actual number of cases with section 275 applications for various reasons, including:

- the manner in which the data was collated was not robust, and staff in some sheriffdoms seemed more likely to notify us of cases than others which was not commensurate with the likely volume of sexual offence cases in those sheriffdoms

- almost half of the cases identified were summary cases, but we heard in our interviews that applications at sheriff and jury level are much more common than at summary level

- only 11 cases at both sheriff and jury and summary levels were identified, but SCTS data suggests that during the same period, there were 20 cases at sheriff and jury level alone.

237. We chose to review all 11 cases that had been identified.

Guidance and training

238. The Crown's general approach to sections 274 and 275 ought to be the same regardless of the forum where a case is heard. This is because the protections afforded to complainers in sexual offence cases apply equally in the Sheriff Court as they do in the High Court. While the most serious offences are tried in the High Court, serious sexual offences may also be tried in the Sheriff Court – one of the Sheriff Court cases we reviewed, for example, featured a charge of sexual assault with intent to rape. We would therefore expect Local Court staff working on sexual cases to have the necessary awareness and understanding of the legal protections afforded to complainers regarding sexual history and character evidence, and that they are familiar with COPFS policy and guidance.

239. While COPFS guidance on sexual history and character evidence is equally as available to Local Court staff as to High Court staff, the guidance tends in places to be more targeted at those working in the High Court. For example, the guidance refers to roles and processes that exist in the High Court but not Local Court function, requiring Local Court staff to tailor aspects of the guidance to their own role.

Sheriff Court case review – Headline findings

Sheriff court case review findings

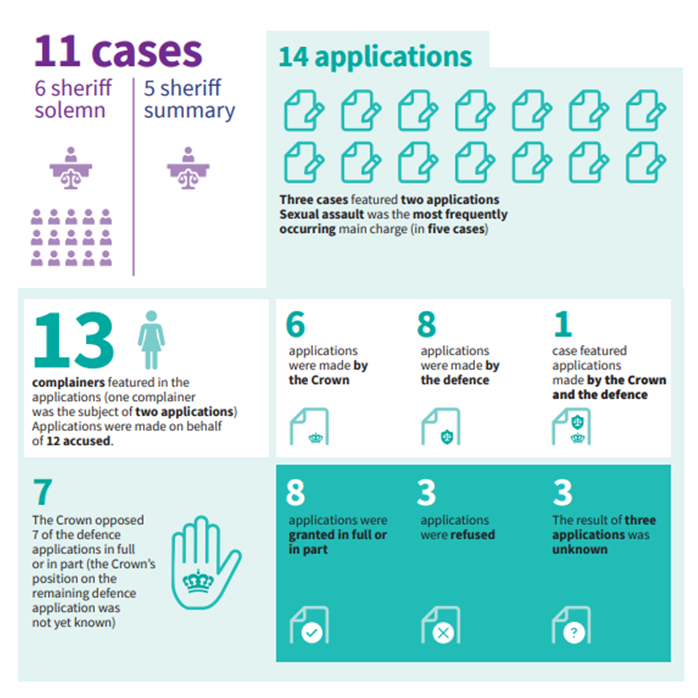

11 cases

6 sheriff solemn

5 sheriff summary

14 applications

Three cases featured two applications Sexual assault was the most frequently occurring main charge (in five cases)

13 complainers featured in the applications (one complainer was the subject of two applications) Applications were made on behalf of 12 accused.

6 applications were made by the Crown

8 applications were made by the defence

1 case featured applications made by the Crown and the defence

7 The Crown opposed 7 of the defence applications in full or in part (the Crown’s position on the remaining defence application was not yet known)

8 applications were granted in full or in part

3 applications were refused

3 The result of three applications was unknown

240. During our interviews, we found there was a variable level of knowledge about sections 274 and 275 among deputes and case preparers working on sheriff and jury cases. Most were aware of how to find the guidance, but were not familiar with the detail of it. In contrast, solemn legal managers – who supervise deputes and case preparers – had a good level of knowledge of the relevant law and guidance and provided oversight and scrutiny of their staff's cases.

241. Among those working on summary cases, we found knowledge of the law on sexual history and character evidence to be more limited. This is likely because section 275 applications are less common in their work, and also because staff working on summary cases are more likely to include trainee deputes and legal staff undergoing accreditation. However, some legal managers at summary level were also unfamiliar with the Crown's guidance on section 275 and were not aware of the common scenarios in which a Crown section 275 application may be required.

242. Staff working on High Court sexual offence cases were initially prioritised for the bespoke section 275 training developed by COPFS.[84] This is understandable, given the frequency with which they are required to manage applications. We are pleased to note that the training has now been made available to others and that a recent course had been well attended by those working on sheriff and jury cases. We welcome the initiative taken by some solemn legal managers to ensure that their deputes who work on sexual offence cases attend the training. We would encourage other solemn legal managers to do likewise. We would also encourage summary legal managers to attend, so they are able to act as a safeguard within their summary teams in identifying cases where sections 274 and 275 may be applicable.

Process for managing section 275 applications

243. Whereas section 275 applications require to be made not less than seven clear days before the preliminary hearing in High Court cases, applications in all other cases require to be made not less than 14 clear days before the trial diet. During our interviews with Local Court staff, we heard that it was rare for an application to be lodged close to trial and that almost all applications are lodged well in advance of the time limit.

244. We heard that nearly all applications are at least identified at the 'first' first diet. They may be dealt with fully at that hearing, but are more often decided at continued first diet hearings. While it is not generally good practice for first diets to be continued, this approach has nonetheless allowed the Crown more time to engage with complainers about section 275 applications (compared to the time available in High Court cases). We did not hear of, or review, any Sheriff Court cases in which staff were under pressure to precognosce complainers about applications within an unrealistic timescale. This gives Local Court staff greater flexibility to engage complainers about section 275 applications in a manner that is sensitive to their needs and personal circumstances.

245. During our inspection, we found little evidence of late lodging of applications in the Sheriff Court by either the Crown or the defence. We did note, however, that even where applications were raised timeously, some were not decided until the trial. This had the unfortunate effect of delaying a decision on a section 275 application for several months, and meant that the complainer was not informed of the outcome until very shortly before they gave their evidence.

246. At summary level, COPFS uses checklists to ensure they are in a sufficient state of preparation for intermediate diets. The checklists cover a range of issues, but there is no mention of section 275. While section 275 applications are rare at summary level, including them on the checklist, alongside other existing issues such as vulnerable witness measures, would be a useful safeguard to ensure sexual history and character evidence is considered.

247. We found the Crown's record keeping in Sheriff Court cases to be significantly better than that in High Court cases. Almost every case we reviewed had key documents stored in a single, easily accessible location. Unfortunately however, at Sheriff Court level there is not the practice of court interlocutors being sent by the clerks to COPFS.[85] Thus, no case file contained any official court minute detailing the court's decision on a section 275 application and its reasoning. There was therefore a reliance on notes made by the depute in court. These notes varied in detail and accuracy, meaning it would be difficult for any colleagues who subsequently prosecute the case to know the court's decision on the application, its reasons and details of any restrictions or conditions imposed.

Engaging with the complainer

248. Unlike in High Court cases, general precognitions of the complainer are relatively rare in Sheriff Court cases. Instead, a precognition of the complainer in relation to a section 275 application may be the only engagement of that type that the complainer has with COPFS. In High Court cases, we heard that case preparers generally make direct contact with the complainer regarding section 275 applications and that the precognition will often take place immediately upon contact. In contrast, we heard that in Sheriff Court cases, the complainer was usually first contacted by a VIA officer who is already known to the complainer and a precognition is then scheduled. This afforded the opportunity to schedule the precognition at a time to suit the complainer, and the opportunity for a support worker to be in attendance if desired.

249. Precognitions of complainers about section 275 applications were carried out by a range of staff working on Sheriff Court cases. This included case preparers, procurator fiscal deputes (including those who prosecute the case at trial) and solemn legal managers. We were surprised to hear of cases where VIA staff were emailed a list of questions to ask the complainer regarding section 275 applications and were effectively conducting a precognition themselves. This is not appropriate as VIA staff lack the requisite training to do so. Generally, we found from our interviews and case review a good level of communication between VIA and case preparers, deputes and legal managers in relation to engaging the complainer about section 275 applications. This demonstrated a coordinated approach to organising and carrying out section 275 precognitions.